Written by Stuart Blackie | Senior UX Designer, Mantel

Good design principles are deceptively difficult to get right.

There’s a delicate balance between crafting a principle that looks good on a Post-it wall or in a presentation, and one that’s strong and actionable — something that genuinely drives excellence for both customers and the business. The steps to create the latter aren’t always clear, and as designers, we often blur the lines between different types of principles, which only adds to the confusion.

In this article, I’ll attempt to cut through that uncertainty. I’ll explore the various types of product design principles you’re likely to encounter throughout your career — what they are, when to use them, and why they matter. More importantly, I’ll share a blueprint for how to approach the task of crafting effective design principles for your team or your entire organisation, drawing on real examples — both good and bad — from across the industry.

What are product design principles?

”Product design principles are value statements that frame design decisions and support consistency in decision making across teams working on the same product or service.

Nielsen Norman Group, 2020

How can they be broken down?

Broadly speaking product design principles can be broken down into three different categories, that being the individual, the team and the business. Whilst each one flows through into another to a certain degree, these are seen as quite distinct with specific use cases that will ensure they are leveraged properly.

Industry Principles (Usability Heuristics): These are best used for individuals to measure their designs at an industry level and ensure that they are meeting well established criteria and benchmarks within the design community.

Design Team Level Principles: These principles are more specifically focussed towards the industry and company. They provide guidelines around how to approach design at a product and brand level, helping to streamline the decision making process.

Business/Program Level Principles: These don’t specifically guide the individual actions of designers but allow those in senior decision making roles to effectively assess the relevancy and efficacy of a project before undertaking it.

Further on in this article I will define each of these principle types more in-depth.

Industry Principles (Usability Heuristics)

Often labelled as usability heuristics — these are to be used at an individual designers level to help structure their work and craft the best experience for customers. These are best used to measure design at an industry level and ensure that you are meeting well established criteria and benchmarks within the industry.

Like many designers, for a long time I would default to Nielsen Norman as my key heuristics of choice. Whilst they are an excellent choice in a variety of circumstances there are so many other different industry level principles that you can use that will form the basis of a high quality design experience. Which one you choose will depend on your project and the outcomes that you are looking to achieve.

How do we define usability?

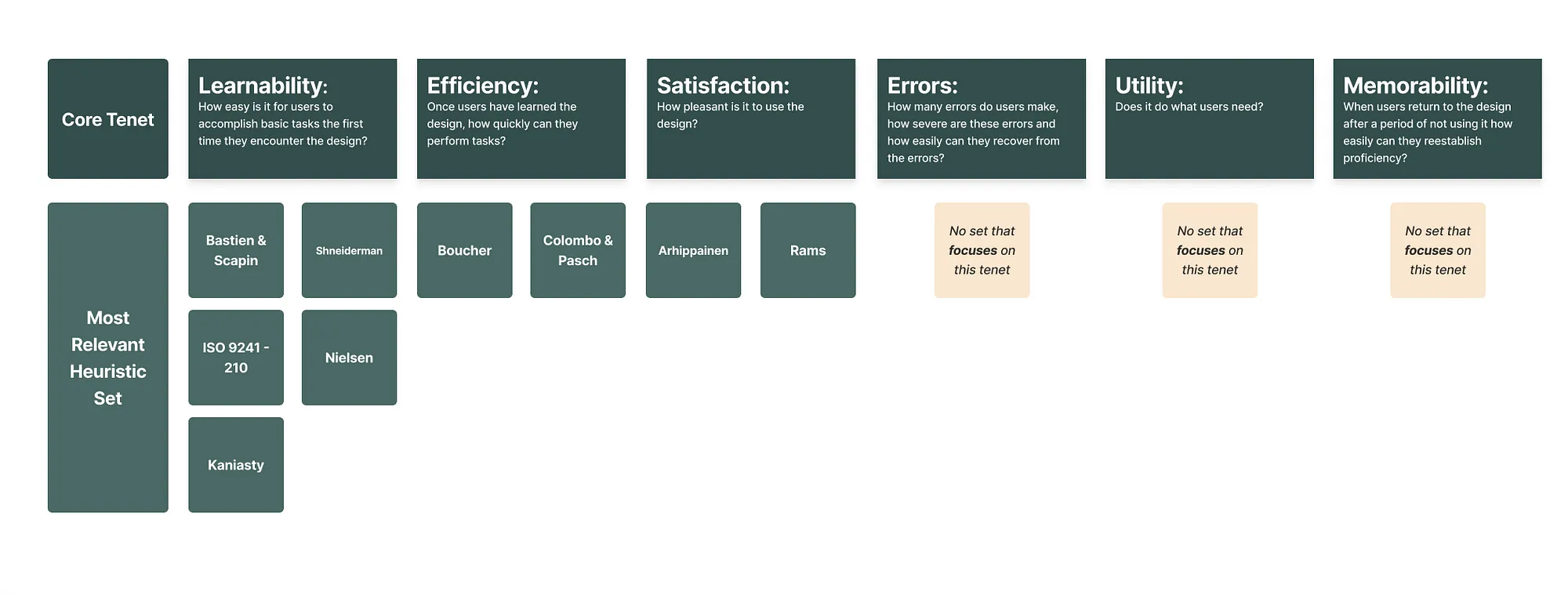

Usability is generally defined by 6 core tenets that guide user interactions.

- Learnability: How easy is it for users to accomplish basic tasks the first time they encounter the design?

- Efficiency: Once users have learned the design, how quickly can they perform tasks?

- Satisfaction: How pleasant is it to use the design?

- Errors: How many errors do users make, how severe are these errors and how easily can they recover from the errors?

- Utility: Does it do what users need?

- Memorability: When users return to the design after a period of not using it how easily can they reestablish proficiency?

Most frameworks cater for the majority if not all of these core components, however, they tend to be more biased towards the first three.

Choosing the right industry principles for you

It is worth mentioning the below Medium article, for which much of this information on Industry Principles has been aggregated:

Usability heuristic frameworks: which one is right for you? by Michael Kritsch

This article dives deep into the different sets of heuristics that exist and which situations to use them, also covering the topic in much more detail than I will go into in this article. However, for a high-level summary please see below.

In essence the core recommendations here are:

To focus on Learnability, utilise frameworks such as Nielsen, Shneiderman, ISO 9241–210 and Bastien & Scapin.

To focus on Efficiency, use a framework like Boucher’s or Colombo & Pasch’s

To focus on Satisfaction, focus on frameworks such as those from Arhippainen and Rams.

For the most well rounded approach the recommendation in most circumstances is to focus on utilising Bastien & Scapin along with ISO 9241–210.

Errors, Utility and Memorability do not have any principle sets that retain them as a core focus, yet aspects of these tenets are covered by the majority of those mentioned above.

However, despite these recommendations, there is no correct answer in this space. Depending on the desired outcome, any variation of these principles is appropriate and can be mixed and matched to focus on the best outcome for your users and their goals. To get more information on the individual principles and depth into Kritsch’s methodology I do highly recommend viewing the article that I linked above.

Team Level Principles

These principles are to be used at a design team level to help structure and craft the best experience for customers based on the specific context of the business and problem space you are solving for. These principles are unshackled from targeting basic tenets of design (heuristics) as well as engrained / expected processes within our industry, and as such there is more opportunity to have a bit of fun with these.

Unlike industry principles there can be a level of immeasurability to them, as their core goal is essentially to provide a guideline to assist designers within their decision making process, whilst accurately reflecting the brand and its customers. In this way, team level principles can somewhat act as prompts to help push your design team and challenge them to dive further into the design. They should provide reassurance, essentially creating light borders around designer creativity, ensuring that we have the freedom to explore with confidence, knowing where we can push to the limit for the customer, whilst ensuring that our work will overall align to the larger picture of design within the business’ context.

What makes a good team level principle?

At face value, there are endless ways that you could approach writing out principles, but in essence there are a few core components that ensure your principles will remain consistent, dependable and strong.

Opinionated: Each principle should be clear on which experience standard it advocates for and why. If the principle is ambiguous about what it recommends, then it could be interpreted differently.

Inspire empathy: Principles should always keep the user in mind — ensuring that they are at the forefront of the decisions that are made.

Clear and concise: They need to be short, unambiguous and to the point to make sure that they are well understood.

Memorable: Principles should be memorable and impactful. Simultaneously, the number of principles should be minimised to ensure that they are effectively recalled and used.

Non-conflicting: Each principle should be dedicated to one experience standard only and not contradict one another.

Reflective of brand: Each principle should speak to the values that your brand seeks to uphold and the image it whats to present to the world.

Creating your principles

So now you know what forms the backbone of a strong team level principle, but how do you begin to create them?

- Know your customer: Research, research, research. Talk to your customers and understand what it is that they value about your brand and within their digital experiences. Different customer bases can have completely opposite value sets so there is no one size fits all approach here

- Know your business: Businesses have goals and requirements that mould their perspective of customers as well as the direction of certain products. There is important context within these goals that always needs to be considered, otherwise it will be impossible to align the user needs with that of the business

- Get it on paper: Discuss the themes with teammates and begin to ideate and get down ideas for what the principles could be. Formulate an opinion and tone of voice that you want to run consistently through the project.

- Get feedback: All angles need to be considered and it is important to run these goals past important stakeholders to gain their perspective and see how it aligns with the business needs as well as those of the customer. Presenting these back with the research that informed them is a strong way for you to reflect and analyse as to whether or not these principles align with your finding as well. Stakeholders in this instance will most likely be people heading up design, marketing, content and tech, however, the actual business units will be specific to your solution space.

- Refine your ideas: Take onboard the feedback that you have received. Ask yourself questions such as do these principles feel true to the product, user and team goals? How does their tone align with the brand and team’s expectations? Refine your ideas to align to key feedback and core questions before continuing the cycle of steps 4 and 5 until you reach a consensus across teams.

It is important to stress the difficulty and oftentimes the length of this process. Whilst on paper it may seem relatively straightforward, presenting these ideas to the right people at the right time is not, and significant time and consultative effort are required to ensure you get these principles right.

More than any other step the solicitation of feedback at all levels is most important. Stakeholders that don’t feel consulted — or who feel that your principles miss the mark on the shared business goals — are unlikely to truly embrace them. Don’t be dissuaded by multiple attempts at getting them right, as securing genuine team buy-in is the ultimate objective to ensuring that your principles are embedded within the business’ culture and will have their intended impact.

What makes a team level principle work?

To understand what good looks like firstly we need to understand why some principles fall flat.

Take these principles from the UK.gov site. Whilst some of them have merit, the overarching problem that exists here is that these principles are quite generic and align with common best practice, rather than feeling unique to the business.

For example:

Design with data / Start with user needs / Understand context: All good designers these days should design with data/research or focus on user needs within their decision making. Similarly all designers should understand the context of their work as an onboarding to their project. Stating the obvious takes up space and prevents you from addressing the real problems that your customers are facing in your specific domain.

Do Less: This principle focuses on the reuse of processes and designs within future products. In an industry context this forms the basis of a design system and reusable internal resources and as such is more inline with best practice now than it being something that will help drive the business forward.

Whilst both these examples aren’t inherently bad callouts and good reminders for design teams, principles should really be reserved for core decision making tools that will help to drive business goals and target customers at a level that is unique to that business.

So what does good look like then?

To try and reinforce the point of what makes a valuable principles I have collated the following examples:

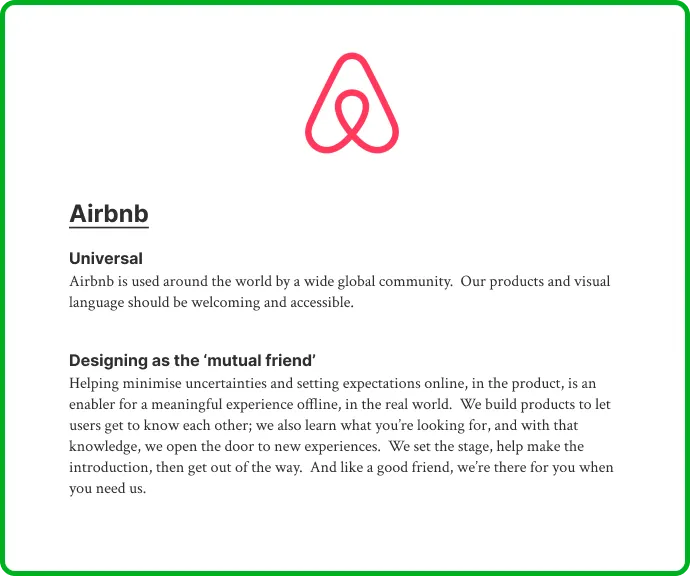

Airbnb

These principles are good as they are enveloped by the context of the company and are symbolic of the brand that Airbnb want to convey to their customers. Likewise, they don’t feel cookie cutter or have much, if any, crossover with industry principles. They are powerful as they provide some constraints to designers, yet simultaneously don’t feeling like a checklist of considerations, offering a voice and perspective on their goals that is uniquely their own. For example:

‘Universal’ is a good principle as it is aware of the broader context that surrounds Airbnb — being that of an internationally reaching company that needs to facilitate communication between people of all cultures and backgrounds. This challenges designers to think in more culturally nuanced ways and consider the impact and requirements of their product in all corners of the globe. Placing a uniquely coloured lens over the decision making process to ensure designs marry up with brand standards and their diverse set of users.

‘Design as the mutual friend’ is another great principle as it emphasises the value of expectation setting and how Airbnb’s digital experience is only really in place to facilitate more tangible outcomes such as real world interactions. This is a core element of Airbnb’s business model and helps to facilitate connection and value to the customers and hosts alike over the long run. A principle such as this places value on communication and expectation setting, challenging designers to think as to how they can work to achieve a seamless transition between the virtual and the real — providing instant value in their design decision making process.

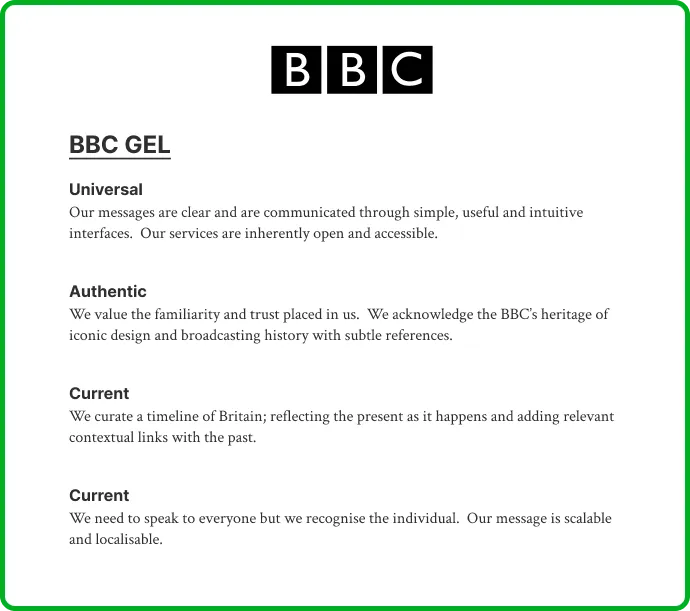

BBC GEL

The BBC serves a diverse community of viewers and readers not just in the UK but across the globe. As custodians of news, the character of their content is equally as important as the experience people have consuming it. This is emphasised through their principles:

Authentic / Current: As the national broadcaster of Britain, the BBC has a long and storied history, which it tries to reflect within its principles, whilst also looking to the future. Paying homage to these traditional roots, the principles of ‘Authentic’ and ‘Current’ allows designers to utilise well-treaded design guardrails, whilst not feeling restrained by them. There is a sense of movement and modernity within these principles, carving a forward direction whilst ensuring that for lifetime consumers there are still links back to it’s heritage to maintain the credibility that has been built up by the organisation over the years.

Local / Global / Universal: Similar to AirBnb, the BBC recognises their diverse audience and targets ‘Universal’ and ‘Local/Global’ as two of their principles, including the context of their position as a national broadcaster and that it is part of their responsibility to ensure accessibility to their content. Whilst factors such as accessibility are often a baseline requirement for many designs these days, it is important to note that for some organisations (especially national/government) it is more of a priority and requirement than others, and referencing it within principles can help to enshrine this as a core tenet of the customer experience.

As you can see, the power of these principles relies so much on the specific context of the customer and business. The way that these have been structured essentially allows these companies to interweave design principles with business goals, setting soft but unambiguous guidelines to challenge for more creative solutions. Through their inclusion, designers can make meaningful in-roads into providing value and points of difference within their customer experience and overall help to drive an effective decision making process for their teams.

Business Level Principles

Business/program level principles don’t specifically guide the individual actions of designers but allow those in decision making roles to effectively assess the efficacy and relevancy of a project within a business context before proceeding with it. These principles are distinct from corporate values or mission statements and should speak to all parts of the business (design, tech, sales, commercial etc.), at their core though they should be focussed on providing the customer an exceptional experience.

These principles guide organisations in project planning, decision-making and aligning design efforts with broader business goals. They need to ensure that design is not just about aesthetics or usability but also contributes to long-term growth, customer satisfaction and market differentiation, providing memorable guideposts for the best way for a business to pursue its strategic objectives.

By and large, designers will never have to deal with these principles within their day to day pipeline. However, for designers working with executive leadership teams and middle management, helping to generate these designs for broader business use can be a core tool in your arsenal to ensure at the highest level the customer and design as a discipline has a voice at the table.

What makes a good business level principle:

The process of writing a good principle is relatively universal, which consequently means that the core components of what makes a good team level principle also apply at a business level as well. On top of that there are a few other factors that need to be considered as well.

Universal yet adaptable: It should be broad enough to apply across different products and teams but flexible enough to allow context-specific execution. Eg: “Prioritise accessibility and inclusivity in all design efforts.” (This can apply to a website, a product, or even a physical retail experience.)

Facilitate collaboration across the business: Projects are rarely done within isolated business units. Strong principles promote cross-functional collaboration across departments.

Not grounded in any technology type or specific solution: Technologies come and go as well as business frameworks and approaches to running organisations. Good principles should remain agnostic from these, looking at building a holistic picture of achievements, rather than a specific way to approach it.

Open to iteration: No principle is flawless, allowing them to be iterated on and evolve over time is integral to ensuring that businesses can grow and change as markets and customer expectations do.

How does this look in practice?

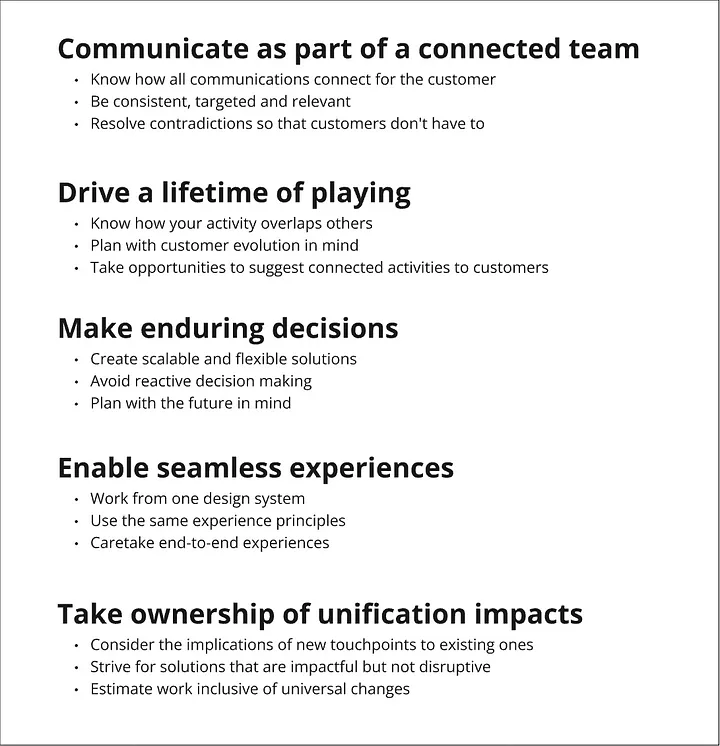

Having scoured the internet I can tell you that principles of this nature can be difficult to find as they are less likely to be used as a promotional tool. What I can show though is an example of some principles that I created within a previous engagement with a large sporting body:

Due to the implications these principles have across the entirety of a business, it is important for them to be broad by nature, whilst still providing enough direction for project managers and business units to measure up the efficacy of projects in their totality.

As with other examples, simplicity and clarity is key as the more complex, the less memorable and the less likely they are to permeate into the organisational psyche.

In the context of these principles in particular, they worked to specifically address situations where the business was currently suffering. For example: cross unit collaboration across design, tech and marketing was rare, with their specific callout here, engraining an expectation for managers to improve communication and holistic business understanding within any project that was up for discussion.

These principles provided a solid foundation to improve the decision making process across middle management teams and their leaders, however, the process and their core tenets could equally be replicated as you move higher up the food chain into the executive branch as well.

Conclusion

Design principles are something we encounter at every stage of our careers — from freelancers trying to break in, to Chief Design Officers leading at scale. While their impact often depends on the team’s willingness to embrace them, principles should never be seen as restrictive. Instead, they’re tools that help us and our teams do our best work — offering clarity, focus, and guardrails that serve both the business and the customer.

When used as intended — and crafted with intention — they become a powerful force for alignment, quality, and growth.

Happy designing.