First up, what is Design Thinking?

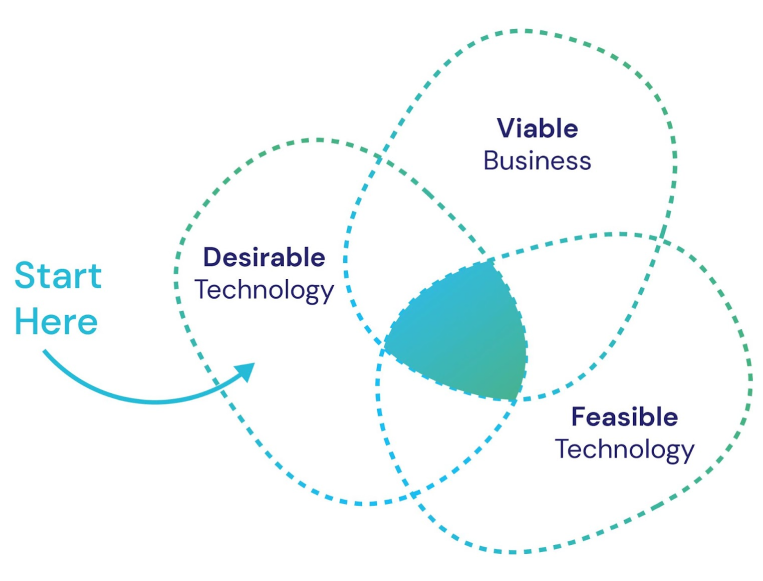

Unfortunately, there are multiple ways to define design thinking, which can cause a bit of a headache! For many designers it is a creative approach to solving problems with the end-user in mind, however it’s finding that sweet spot where the solution is not only desirable for the customer, but also technically feasible and viable for the business.

Companies such as IBM, Samsung, Puma and Philips actively use a design thinking approach to solve ambiguous problems and to improve their products and services. Teun Den Dekker, Dutch author of the 2020 best selling book ‘Design Thinking’, describes design thinking as a way of thinking, a way of working, a way to approach projects and a toolbox.

This approach is not reserved only for the technology space or for product design and innovation, design thinking is also effective in a multitude of other environments where the need for designing better services and customer experiences is important, including government and public services, education, health and the social impact space.

So where did this whole design thinking thing come from?

What are the origins of Design Thinking?

Whilst IDEO are not the inventors of design thinking, they are seen to be a leader in the design thinking space. IDEO founder David Kelley believes that it is creative confidence that allows everyone to solve problems like a designer. It is a common misconception that design thinking is a somewhat ‘new’ way of thinking- it’s more of a new mindset approach. The idea that anyone can apply a designer’s mindset to creatively solve all types of problems is relatively new.

The origins of design thinking are multi-faceted, with engineering, natural sciences, social sciences, business and the fine arts all having an influence in shaping design thinking into what it is known as today. But if we look back to 367 BC, Plato had the mindset of a designer. Through the voice of Socrates in his book ‘The Republic’ (367 BC) Plato suggests that the users of products are the ones who are best positioned to judge the quality, beauty and usability.

“It must follow, then, that the user of a thing has the widest experience of it and must tell the maker how well it has performed its function in the use to which he puts it” (Socrates, 375 BC).

Jump forward many (many, many) years later…

1960’s

The scientist Herbert Simon proposed the concept of ‘simulation’ (prototyping) in order to produce the right solutions. He also emphasised the importance of having a problem that was understood by all.

“To understand them, the systems had to be constructed, and their behaviour observed”. (Simon, The Sciences of the Artificial, 1996)

Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber, professors of Design and Urban Planning at the University of California at Berkeley, coined the term ‘wicked problems’ to describe the challenges of solving social policy problems. According to Rittel and Weber, wicked problems constantly change, have many root causes and to top it off there isn’t always one ‘right’ answer. That’s pretty wicked.

“Part of the art of dealing with wicked problems is the art of not knowing too early which type of solution to apply” (Rittel & Webber, 1973).

1980s-1990s

UK author and professor Nigel Cross saw design as a discipline distinct in itself, not one which had to rely on any other field. Cross believed the designer was a central cog in the design thinking process, and also noted that the process was more about building ‘creative bridges’ to solve problems.

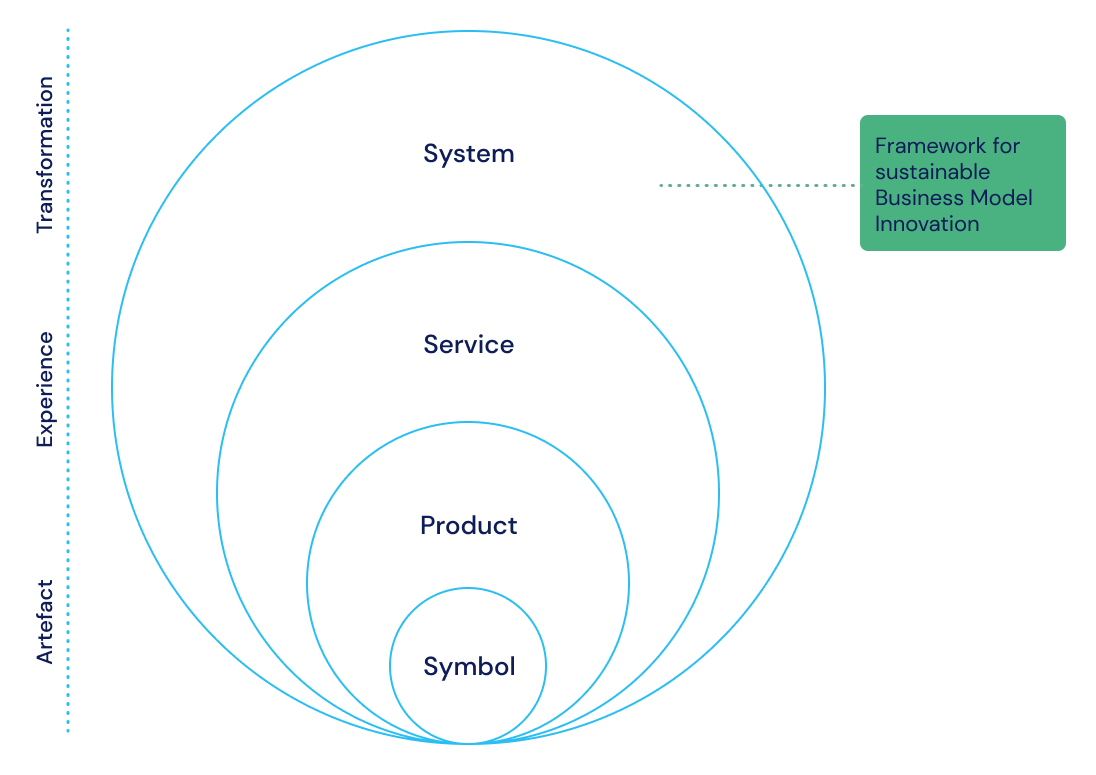

Then along came Richard Buchanan, professor of design and author. He popularized the notion that design thinking can be used as a framework to solve those ‘wicked problems’, so named in the decades prior by Rittel and Webber. He is also credited with identifying the Four Orders of Design: signs and symbols, objects and artifacts, interactions and experiences and systems.

Like many before him, philosopher and theorist Donald Schon, in his book titled The Reflective Practitioner, was keen to point out that design should not have to rely on the sciences to be taken seriously. One of the most imperative impacts Schon had on design theory was his belief that ‘problem setting’ was crucial in ensuring that designers took the correct approach.

Today

Don Norman, one of the founders of Nielson Norman Group, was the first person to coin the term ‘user experience (UX) design’ and is considered to be one of the greats in the world of Human Centred Design. When working at Apple, he took into account the experience of users, from when they first purchased the product at the store to the unboxing experience of the user, as part of their journey. By observing the user’s interaction with all aspects of the product, the design, the interface, and the manual, it provided Norman the opportunity to design an experience that better addressed the needs of the user.

“Good design is actually a lot harder to notice than poor design, in part because good designs fit our needs so well that the design is invisible, serving us without drawing attention to itself. Bad design, on the other hand, screams out its inadequacies, making itself very noticeable” (Norman, The Design of Everyday Things, 2013).

What are the Principles in the Design Thinking Process?

So now you know a little of its history, how do you actually apply design thinking in practice?

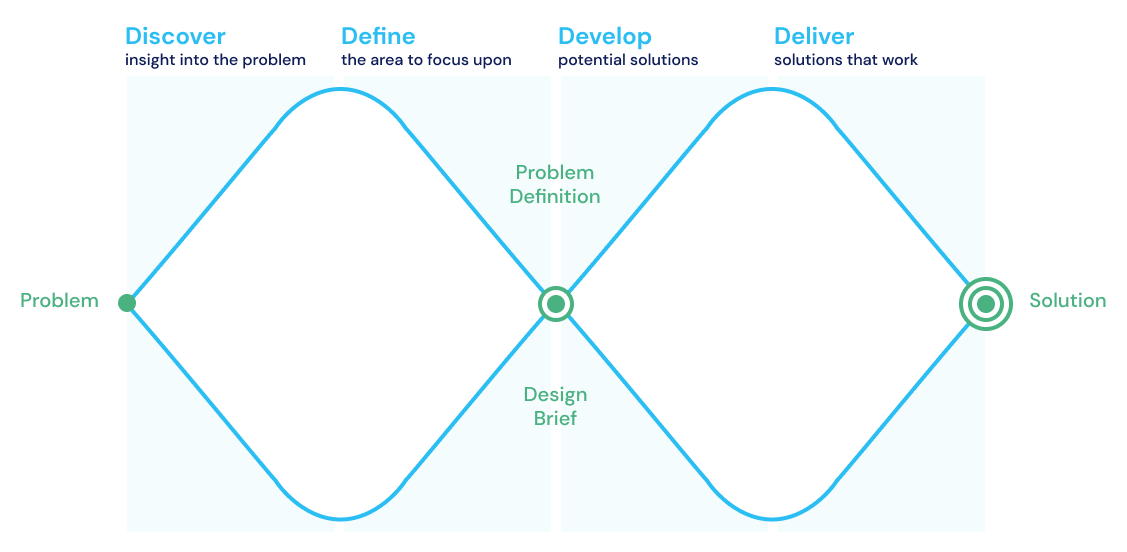

The design thinking process is not linear, but instead iterative, involving many feedback loops and creative cycles of diverging (casting the ideas net far and wide) and converging (focusing ideas in). Some approaches to design thinking include the “Double Diamond” approach (discover, define, develop and deliver).The double diamond approach is a visual way to help you to navigate and understand the design thinking process.

Empathise

Know Your Customer

At this stage, research is conducted to allow you to develop a deep understanding of your customers’ and stakeholders’ contexts, needs and expectations.

In the instance of customers, this might involve interviewing your customers to understand how they currently use a product, what their pain points are and what they need or expect from a product or service.

In the instance of service stakeholders, this might involve interviewing the stakeholders that help an organisation provide their customer service to understand their role in providing the service, what their pain points are and what they need to do their job better.

Understanding your customers’ and stakeholders’ needs and pain points allows you as a designer to empathise with them, and keep their needs at the forefront of your mind when designing a solution that’s relevant and appropriate.

Define

Hypothesise and Define

In the define stage you want to be able to clearly articulate the problem you want to solve and settle on one challenge to take forward.

Once you have an understanding of your customer, it’s time to start hypothesising and defining the problem. “A problem statement is a concise description of the problem that needs to be solved” (Rosala 2021), and is created by teams as a way for the team members to align on the scope and expected outcomes of a project.

At this stage, it may also be useful to map earlier user research data into a customer journey map. Journey maps outline your customers’ journey, highlighting their interactions with your product or service along the way, and include any pain points or delight points, as well as highlight any potential opportunities for improvement.

Ideate

Explore the Possibilities

The ideation stage is the fun part. Time to get those creative juices flowing and capture as many ideas as possible. You could get your team together and have a time-boxed ‘Crazy 8’s’ ideation session, or arrange a co-design workshop with your stakeholders.

The benefit of collaborating at this stage to generate ideas as a team is that you can explore a variety of ideas that come from a broader spectrum of perspectives. This will be more productive and allow the opportunity to reveal things you hadn’t thought of before, which can make for a better outcome.

Prototype

At this stage you want to create something tangible that you can validate with the people who are going to use it, whether it be a product or service.

This is where prototyping comes into play. Using the feedback from your customers, your understanding of the problem and your ideation concepts, it’s time to create a prototype that you can put in front of the user to get their feedback for improvement.

Test

Validate and Learn

Testing our prototype with users allows us to gather feedback and use this data to refine our concept. Remember what Plato said way back when? This is your opportunity to get feedback from the people in the most relevant position to provide it.

Taking the feedback into consideration, it’s time to go back to the drawing board and update the prototype.

Rinse and Repeat

The cycle of iterating, validating and learning is a process often repeated in a project, as each iteration and layer of feedback unearths new insights to inform greater improvements to our concept.

Conclusion

Starting out with a greater understanding of our current reality through the use of user research is a trademark of design thinking and speaks to design’s data-driven and user-centered approach.

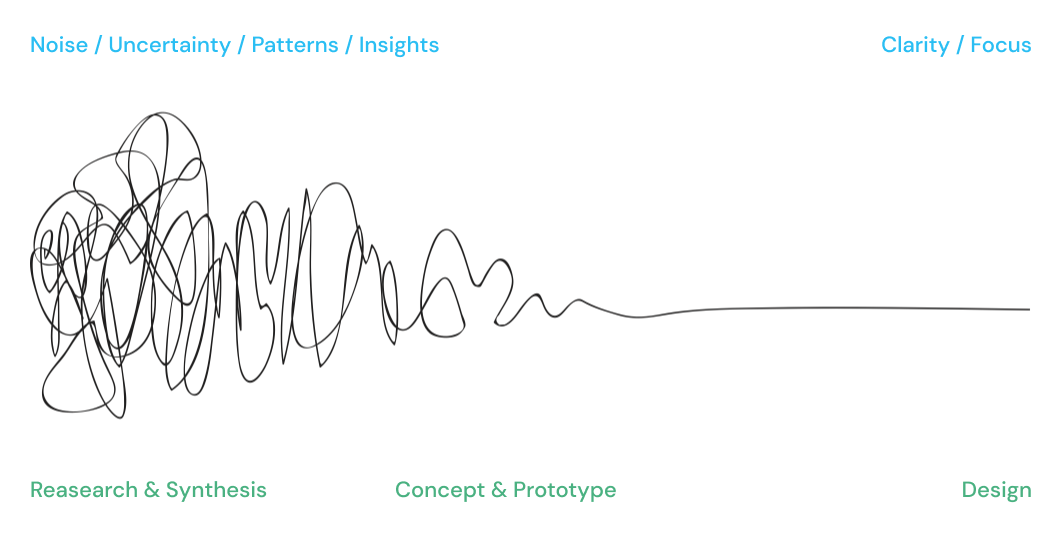

The design squiggle illustrates what this process or approach looks like – and it’s not linear – as designers go from research to concept to design, continually refining towards a solution that is informed by relevant human feedback.

The Design Squiggle – From Ambiguity to Clarity

The design thinking approach can be used to solve all sorts of problems and can be used by anyone – you just need to adopt a designer’s mindset. Understanding user needs is key to this mindset when driving innovative problem-solving and human-centered practices.

References:

Design Thinking (By Teun den Dekker)- By Teun den Dekker, 2021

IDEO :https://designthinking.ideo.com/

The Design Thinking Toolbox : A Guide to Mastering the Most Popular and Valuable Innovation Methods- Michael Lewrick, Patrick Link, and Larry Leifer

Buchanan. (1992). Wicked Problems in Design Thinking. Design Issues, 8(2), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511637

Johansson‐Sköldberg, U., Woodilla, J., & Çetinkaya, M. (2013). Design thinking: past, present and possible futures. Creativity and innovation management, 22(2), 121-146.

Nigel Cross, Designerly ways of knowing, 1982: http://www.makinggood.ac.nz/media/1255/cross_1982_designerlywaysofknowing.pdf

Rittel, H. W., & Webber, M. M. (1973). “Dilemmas in a General Theory of Planning.” Policy sciences, 4(2), 155-169. https://www.cc.gatech.edu/fac/ellendo/rittel/rittel-dilemma.pdf .

Simon, H (1996) , The Sciences of the Artificial https://monoskop.org/images/9/9c/Simon_Herbert_A_The_Sciences_of_the_Artificial_3rd_ed.pdf