This post is part of a series about Cloud Managed DevOps Service at CMD Solutions. This time however, we lift up the curtain a bit and show you how some of what we do works.

When it comes to computers in any form there is one task that it’s hard to find anyone who enjoys it, and that is patching. While updating a system in order to get new capabilities can be fun because of what it will enable you to do, patching means spending time to maintain the status quo. Which is both boring and frustrating. Luckily cloud infrastructure allows us to more easily automate this, so let’s have a look at how that works when running on AWS.

What and why do we patch?

Let’s quickly define what I mean when we discuss patching. In broad terms, there are three reasons to make changes to a system:

- To make it better

- To keep it working as it is

- To fix something that is broken

While there are some exceptions, patching generally covers the last two. Fixing something that is broken is the more common of the two. Most of us are familiar with the monthly patching that comes for our Windows systems, but Linux and macOS instances have their own sets of patches that need to be applied. Often these are security patches and whether they’re caused by issues found in the operating system, an application you use, or even the CPU, is immaterial. Leaving your instances insecure is for fairly obvious reasons not a good thing.

Keeping things working as they are is perhaps less clear, but is still something that happens. An example of this I’ve run into in the past was when a system was running an older version of OpenSSL that didn’t support the latest TLS versions and one day calls to GitHub started failing because that site demanded a later version than what this system had. The fix was a simple case of updating OpenSSL, but it was annoying to have to do so after the fact.

The Shared Responsibility Model

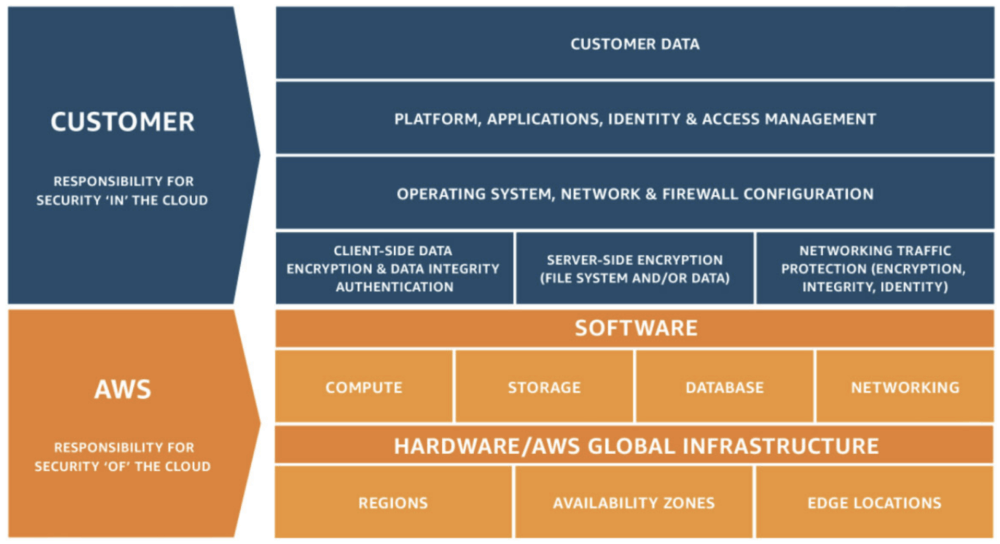

When it comes to AWS, we can’t have a discussion about managing the services we use without mentioning the Shared Responsibility Model.

The Shared-Responsibility Model from AWS defines the parts that they take care of, and those that we as their customers have to handle ourselves. And as you can see in the image, the Operating System of our instances and what’s running on them falls clearly within our responsibility. This means that while AWS can (and does) provide tools to make it easier to do the patching it’s up to us to implement them.

Traditional patch management

As I stated in the introduction, patching is possibly one of the most boring tasks to carry out. I remember the times where I was responsible for maintaining a small set of servers and needed to log into them one by one (when I happened to think of it) and apply the latest security patches. Obviously this doesn’t scale and isn’t good enough, which is likely why tools to automate this have been popular for quite some time.

Especially these larger environments you will have likely moved past this and instead have switched to using management tools like Puppet, Chef, or Ansible that can automate this for you. Then, if you hooked this up to a scheduler of some sort all you really had to do was do some spot checks to ensure that everything works the way you want it to.

Unfortunately, when moving this to a cloud environment it comes with certain downsides. First is the fact that adding instances will take some extra configuration. Yes, you can write a script that generates a list of your instances that need to be updated, but you may also need to install some software on those instances that your tooling requires.

And you need to be able to access those instances. If you have a strategy where you have separate accounts for your workloads and environments (which is highly recommended to lower the blast radius if something happens), that means you either need to run your tooling in multiple places or you need to ensure that every VPC is accessible. Which doesn’t even mention the need for SSH access, something I’ve cautioned against in a series of posts where I mention AWS native alternatives.

AWS Systems Manager Patch Manager

So, how can we do this in a cloud native way then? While the services under the AWS Systems Manager umbrella are very awkwardly named (I don’t think I’ve every given a talk where I didn’t mess up some of the manager names, and I will skip the Systems Manager portion of their names in the rest of this post), they are also very useful for the purpose we’re looking at.

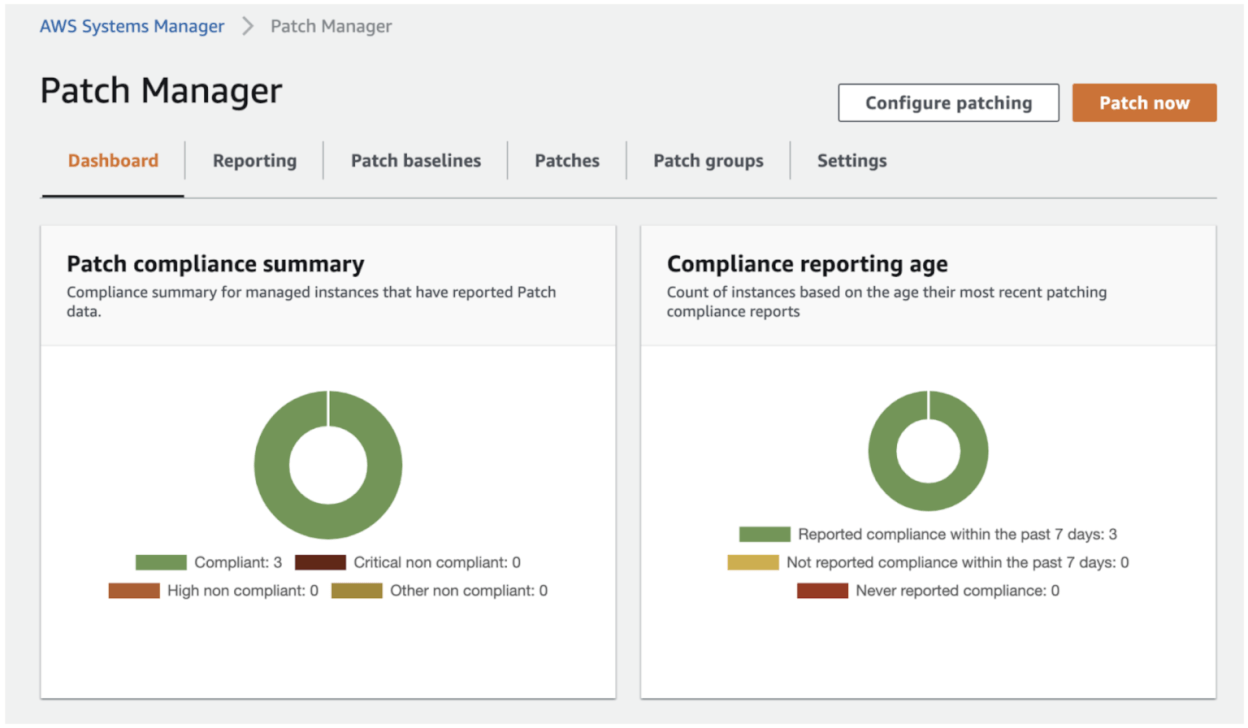

Patch Manager is exactly what its name implies. It allows you to run an immediate patch job on a selection of instances, or set up a schedule to do so. The nice thing here is that from a high level view, Patch Manager doesn’t even care what Operating System your instances are running. As in, whether it’s a Windows, Linux, or macOS instance, it will automatically apply the patches in the correct way for the Operating System.

So, how does this work? First, let’s start with the pre-requisites. As with anything concerning Systems Manager, you need to enable your instances for the service. The official documentation goes into a lot of detail, but there are really only three main things you need to do with your instance:

- Ensure that the SSM agent is installed and running. This is the case by default for many AMIs, see the list here.

- Attach an IAM Instance Profile to the instance that contains the AmazonSSMManagedInstanceCore policy as described here.

- Access to certain S3 buckets. As patches are downloaded from S3, you will need to ensure that you don’t block access to these. This is only a concern if you block or limit access to S3 in some way, as by default you should be able to access these buckets.

Once you’ve done that, the instance will be managed by Systems Manager and you can see it in Fleet Manager. Please be aware that the instance profile needs to be attached when the SSM agent is started, or it may take a long time for it to show up. If you attach the instance later, it may be worth restarting your instance to speed this process up.

Running a single patch job is easily done through the Console, but also when using the CLI. You can simply select instances by tag or even InstanceId:

However, the real value is when you set up a patching schedule. Which you can do by way of a Maintenance Window. Again, setting this up is easy enough using the Console, but let’s instead have a look at how we can do this using CloudFormation.

Admittedly, that looks like a fairly big thing to write and tweak. However, from now on every week on Sunday at 4am Melbourne time it will patch all of our web servers. Which is pretty neat as it means we don’t have to think about that anymore.

And you know what’s even better? Now that we’ve got this set up as a CloudFormation template, we can deploy it as a CloudFormation StackSet and use that to ensure it is automatically deployed to every account in our AWS Organization. Without needing to do anything more.

Patch Baselines and Patch Groups

There is a lot more to say about Patch Manager, and I recommend reading the documentation to get the most out of it, but I will dive briefly into the concept of Patch Baselines and Patch Groups.

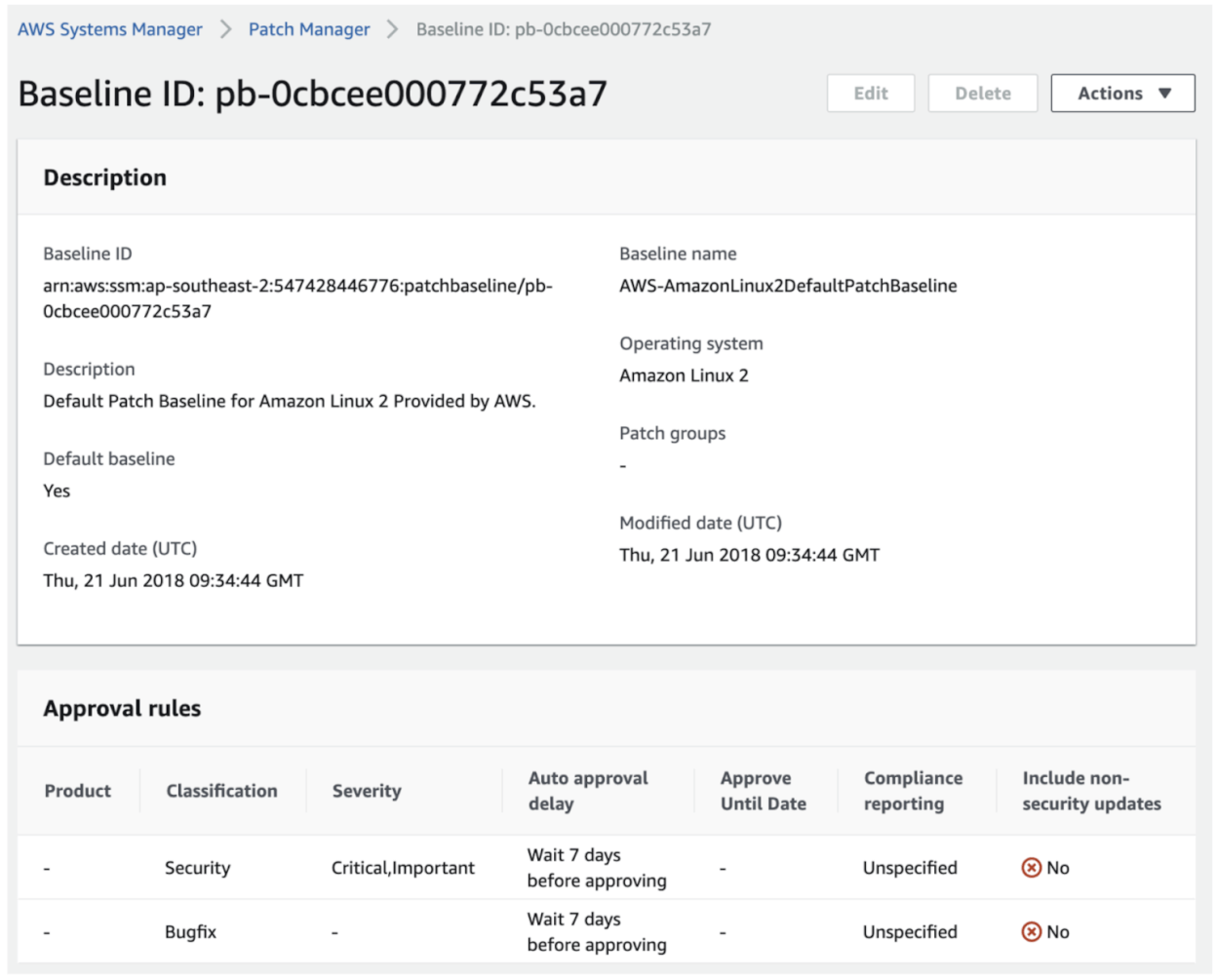

Patch Baselines define how and what is updated. As mentioned earlier, by default Patch Manager doesn’t care about what OS you run and treats them all the same. Under the hood however, it uses OS specific Patch Baselines.

And you can create your own Patch Baselines as well, and set those as the default version for your OS. If you do this a standard Patch Manager run will use the baseline you defined instead of running it separately. Again, if you include all this in that StackSet from earlier, you can easily enforce this throughout the Organization.

A related item is Patch Groups. These are instances defined by a specific tag (Patch Group, with a value of your choice) for which you define a specific baseline. This allows you to, for example, define a separate way of defining patches for certain instances where you can then test that the patches work correctly before they get rolled out to the rest of your fleet instances. You can also set up separate maintenance windows for these Patch Groups, to make it even easier to verify the patches.

For example, you can see in the above default Patch Baseline that patches will be applied after 7 days. This is to ensure that if these patches have any issues, they are detected before they get installed. But if we set up a Patch Group (consisting of some development or test instances) that applies these patches after only a day and runs on Tuesday instead of Sunday, we have most of the week to see if it interferes with our applications.

AWS Systems Manager Automation

Patch Manager is a very useful tool, but it doesn’t solve all of our problems. In particular, while it works well for long-lived instances it isn’t as good for auto scaling groups. After all, if an instance spins up 5 minutes after the maintenance window, it won’t get any patches until the next maintenance window starts and that might be too late.

One way to solve this is by ensuring you always use up-to-date AMIs for your auto scaling groups. For example, you can set up automation that will refresh your auto scaling groups when a new version of the Amazon Linux 2 AMI is released. Or if you build your own AMIs, you can trigger it to use that. There is a lot that can be discussed about this, but it falls outside of this particular post.

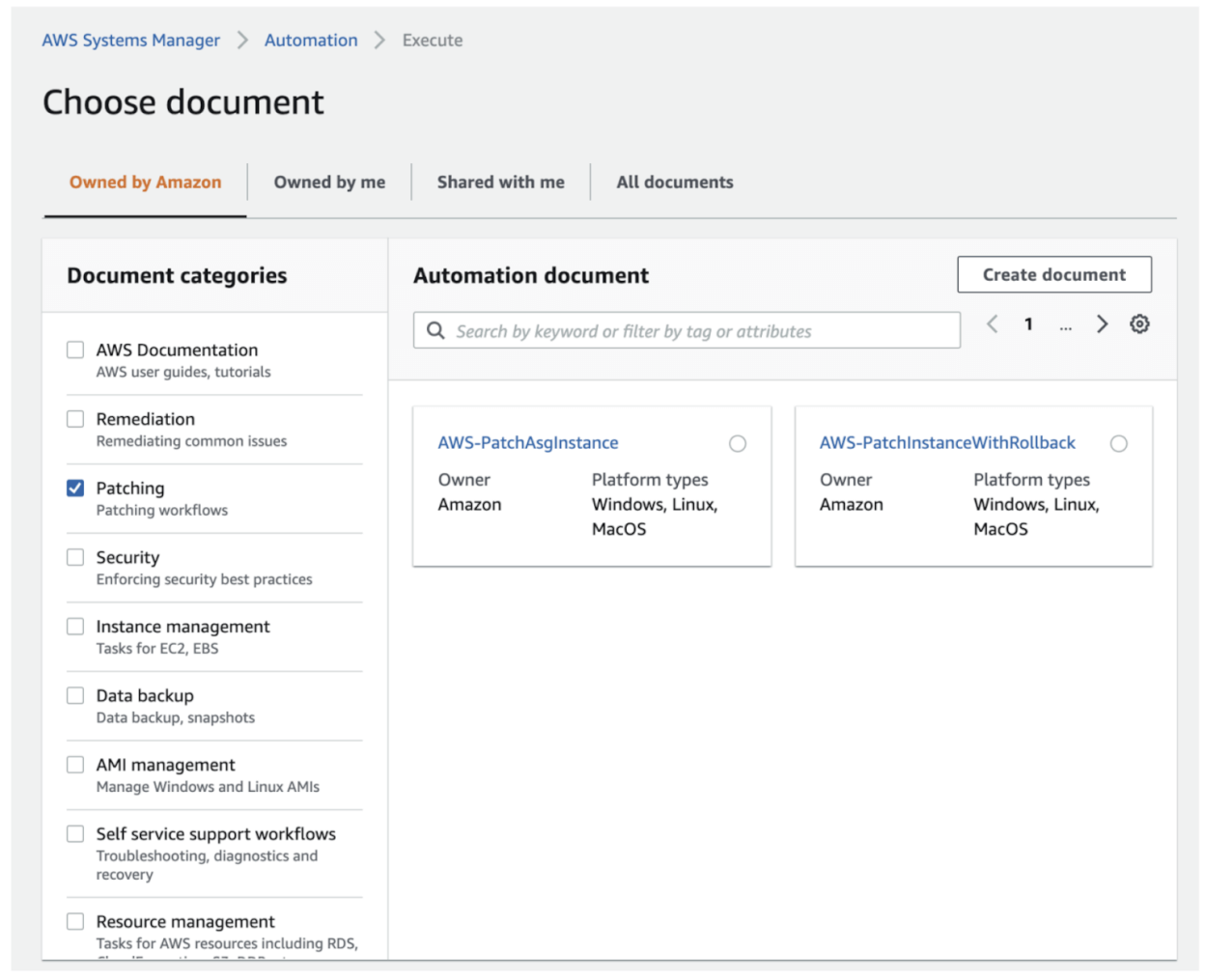

Instead, what I’d like to mention is another way where you use a combination of EventBridge and Systems Manager Automation. Using EventBridge (formerly also known as CloudWatch Events) you can set triggers to run when an instance spins up. Unfortunately you can’t invoke Patch Manager directly, but we can use Systems Manager Automation to do that for us.

There is a runbook (up until recently this was called an automation document) ready to use for this, named AWS-PatchASGInstance that does exactly what we want. Again, if we were to put this into CloudFormation what you’d get is a resource defined as:

Of course, while AWS-PatchASGInstance does install these updates, it does some additional things as well so it’s always best if you have a look at it yourself and perhaps create your own runbook to use instead. In addition, and you likely figured that out already, but this setup would not be limited to autoscaling groups either. Instead, it will run for any instance you start in your account.

Easing the frustration of patching

In the end, yes patching is a bit of a necessary evil. But with the right tools and mindset we can make it a lot less painful. While the examples provided above aren’t a complete solution, they can give you a good start if you want to set up a solution that will patch any instances in your environment that you start up, and then keep them patched on a weekly basis. And, of course, you can adapt the ideas to your own requirements. When it comes to cloud infrastructure, it’s fairly easy to experiment and end up with something that precisely matches your needs.

If you want to read about similar solutions and ideas from our Cloud Managed DevOps Service, you can find links to the other articles here.